Aonarach le Chéile is a new festival focused on solo dance. It is organised in Dingle by Maria Svensson (dance artist in residence at An Lab) and Nick Bryson, with the support of Áine Moynihan, director of An Lab. Intended to take place in An Lab, the sale of An Lab’s host building meant a last minute change of venue to An Díseart, a former convent, leased now as a spiritual and cultural centre. Though still full of its religious heritage, the building’s many spaces were hospitable to the combination of performances, workshops and talks that constituted the festival.

Aonarach le Chéile is a new festival focused on solo dance. It is organised in Dingle by Maria Svensson (dance artist in residence at An Lab) and Nick Bryson, with the support of Áine Moynihan, director of An Lab. Intended to take place in An Lab, the sale of An Lab’s host building meant a last minute change of venue to An Díseart, a former convent, leased now as a spiritual and cultural centre. Though still full of its religious heritage, the building’s many spaces were hospitable to the combination of performances, workshops and talks that constituted the festival.

I was invited to give a talk about my experience of being an independent artist and on the relation between my work and the public. Below is an English language version of what I said (version rather than translation) and I’ll write a follow up post with some further reflections on what this stimulating and heartening new festival achieved.

I want to start with the festival poster image of me dancing, me on my own on Banna Beach. It’s an image that seems to encapsulate a certain view of the solitary individual dance artist, vulnerable to the elements. I want to propose that to it’s a mistake to read the image as signal of independence, and I’ll explain about that in more detail at the end, but more importantly that the idea of an independent dance artist is an unhelpful concept, one that misses the necessary interdependence of creatures, and that risks trapping us in relationships that do us, do others and do our art form no favours. I say this as someone who has called himself an independent choreographer and dance artist for all my professional life, but, looking back, my way of working has always depended on others and my work has evolved to reflect and enjoy that interdependence.

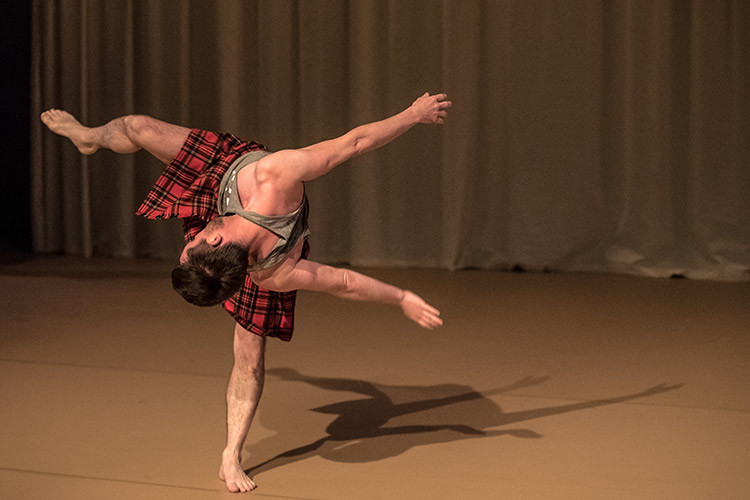

Take for example Cure. It’s a solo performance for me and these images of it might again suggest a solitary figure in the darkness of the stage. But Cure was made, very deliberately, from choreography of six others (who had worked with me on Tabernacle) and whom I commissioned to each make ten minutes of material for me that I integrated into a single work. I loved performing Cure, but the opportunity it gave me to connect to myself was something that was possible thanks to the shaping input of others. Each time I stepped on the stage, I imagined myself as an astronaut doing a space walk – an apparently risky solo expedition but one that was only possible because of the rigorous preparation and training that a whole team of people invested in that individual. I also knew that, like at Cape Canaveral, a whole team watched and supported me from the lighting box, making sure I navigated the solo safely. And that solo endeavour only made sense in relation to the live presence of the people who helped create the work by being in the audience, whose energy was also an explicitly acknowledged element of the performance. My solo was absolutely dependent on a community of support.

Nonetheless the fiction of independence and its associated solitariness came easily to me. The impulse to create through dance wasn’t one I discovered with others. Though the Ring Gaeltacht is well known for its singing and music traditions, we didn’t have a dancing tradition there. As a child I danced with the scoláirí Samhraidh in their nightly céilís and I must have been good at it since I won medals in the end-of-course competitions. But being ‘light on my feet’ was not something that made me feel I fitted in. It was an exception, a deviation, just as a career in contemporary dance was a deviation from what seemed like an academic path when I was studying English at university in England. I know others have a different pathway into dance, maybe discovering it younger than I did, finding easy company and community in regular classes with friends, but that wasn’t my experience. I remember a conversation with David Zambrano who developed the Flying Low technique. He started dancing from social dances in his native Venezuela, so he is used to being in the middle of a community that dances and has a practice often has many dancers milling around a studio. He told me that he never practices alone and only develops solos when he’s dancing in front of people. I met him in residency in Poland where he had thirty people in his studio while I was in another studio on my own. It reminded me that we have our habits and preferences, and as an introvert, being on my own is a familiar and energising state in my life. And that preference may have predisposed me to seeing myself as an independent artist, but it isn’t only about preference.

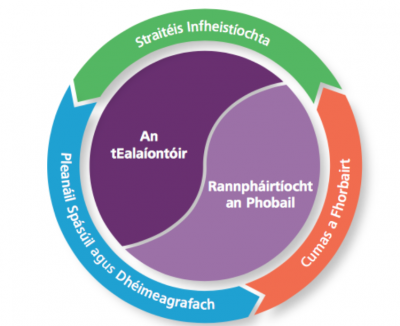

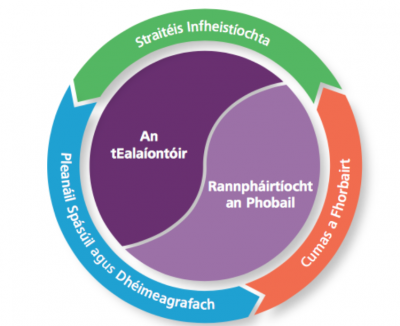

The idea of the lonely artist separated from the generalized mass of the public is a legacy of Romanticism, and as such a relatively recent invention but it’s one that conditions the cultural policy environment in which we work in Ireland. The Arts Council’s new strategy Making Great Art Work sets out two main policy priorities in its ten-year vision: proper resourcing of ‘the Artist’ and a focus on public engagement in the arts. It’s hard to argue with the priorities but they are built on an unhelpful assumption that artists are separate from the public, as this diagram makes clear.

Because it presupposes this separation, the Arts Council has to go to some lengths to hold the separate parts together, with its wraparound priorities of circle of investment, capacity-building and attention to spatial and demographic distribution. Part of the problem is that the Arts Council uses the capitalised abstract and lonely singular Artist to designate the variety of people engaged in artistic practice. It’s an odd choice, given that the strategy document recognises the varied categories of emerging, mid- and late-career artists in its considerations, as well as the different ways and contexts in which artists work. What if instead of conceiving the Artist and Public as separate, we were to recognise that artists – plural and diverse- are part of a plural and diverse public. We use public services, public roads, public hospitals, schools. We pay taxes and vote. We are the public alongside and with others.

To be fair to the Arts Council, this attention to the Artist comes in part from its research on the poor working conditions and precariously low incomes of artists. But again we’re not alone in experiencing those conditions. Precarity is a symptom of a wider pressure in neo-liberal capitalism that has encouraged individualism and self-reliance and discouraged the structures and stabilities that support individuals in community. The celebration of individual freedom from the oppression of restrictive social norms, which is a good thing, has also facilitated a neoliberal economic system that traps us in often exhausting self-exploitation. As a result, instead of being liberated exceptions to the dominant system, the endlessly mobile, adaptable, creative independent dance artists risk being the model of this neoliberal subject.(See for example Bojana Kunst’s Artist at Work or Andre Lepecki on the fetishisation of mobility)

So I want to propose an alternative way of thinking about artists as part of the wider public. The model I have in mind is the brilliant sean nós singer in a community. Everyone has a song, and in group gatherings it’s great to hear everyone’s song, but we know there are some people with a particular ability and gift in singing. And when they sing, they sing for the whole group. Their distinctiveness does not put them outside the group. Nor do they need to diminish their distinctiveness to be connected. If any of you have seen the people ag windáil (literally ‘winding’ the singer by holding their hand and rotating the lower arm from the elbow), connecting physically and encouragingly with the singer, it’s clear that the exceptional gift can be linked and channelled viscerally into, and supported by, a community. That’s the kind of artist I’d like to be in relation to communities that welcome me.

Many of you will have seen Match, the dance film I made in Croke Park. I want to talk about it for a moment to illustrate what I mean about how a dance artist might connect a particular vision to a wider community. Match was a Dance on the Box commission by RTÉ and the Arts Council. I knew it was an important opportunity bring contemporary dance , an artform that has relatively small audiences, to a much wider viewership.

Many people in Ireland might say that they don’t understand contemporary dance, they don’t know how to decode it. However, thousands of people every week watch men and women playing hurling, camogie and football, expressing themselves physically, psychologically driven, emotionally powered and making stories that people will talk about and analyse for days and weeks and sometimes years. Irish people know how to read bodies in those contexts and so by placing a duet on the hallowed turf of Croke Park, I wanted to demonstrate to viewers that they already knew how to read the bodies in action there.

My family are all GAA players and fans: my mother played camogie, my uncles hurling and football, my sisters ladies football, my brother is Waterford county physio and a former underage county player, my other brother is a sports journalist and a trainer of local teams, my first cousin has been in eight all Ireland ladies football finals. By nature and nurture, my body was made for GAA, but I’ve taken that DNA, my inheritance, and given it a different expression in dance. But that different expression does not diminish my kinship to the community from which I come. My family were delighted and a little jealous that in Match I managed to perform on Croke Park before any of them did. And they got it. They helped me with ‘costuming’ authenticity and detail. But putting dance in that iconic territory and, by broadcast on national television into the homes of people who would never knowingly choose to attend a contemporary dance performance, was an important way for me to resist the separation of ‘The Artist’ from ‘the Public’. Unlike soccer players who when they reach the top of their game become so wealthy that they live lives of separate and insulated from the experience of the majority of people, with an amateur game like hurling and football, you can be a star and also the local teacher. Distinctiveness and excellence does not separate you from community. On the contrary, it serves community. By appearing on Croke Park and on the national broadcaster with Match, I wanted to claim the same right to connectedness without compromising the distinctiveness of the vision the choreography offers.

That connection may not be something that people can always articulate. The day after Match was screened it was discussed on the Ray D’Arcy show. One man phoned in to say he had no idea what was going on in the film, but that he couldn’t stop watching it. That suggests to me that he felt a connection to the work, even if he didn’t have the words to express what he felt. And surely we dance because words are not always adequate or available to communicate what needs expression? Dance has the ability to give form and space to the strangeness and surprise that we all harbour within us, as well as the unfamiliar that seems to come from outside of us. In doing so, dance has the ability to challenge restrictive ideas of a homogenous community with clearly defined borders.

Too often, ideas of the public and the community are built on explicit and implicit exclusions. Philosophers (Arendt, Butler) trace this back to the very origins of democracy in Athens, where it is true that citizens could participate in public debate, but those citizens were free men and their ability to show up in public was dependent on the unacknowledged care and labour of women, and of slaves who themselves, alongside resident foreigners, did not count as citizens. As an EU citizen living in the UK, this question of who gets to belong and who doesn’t is currently relevant for me. But it is equally relevant in Ireland where we have a system of Direct Provision that choreographs the marginalisation of people and their potential that could otherwise be contributing to the country, where female bodies are not accorded the same autonomy and respect as male bodies and where the number of families living in emergency homeless accommodation is at the highest level recorded

(The most recent figures show there are now 1,442 families and 3,048 children homeless nationwide in Ireland an increase of 25% from August 2016 to August 2017. See Focus Ireland accessed 17 October 2017). These kind of inequalities are barriers to people’s ability to participate, to be visible and recognisable in public as part of a community, and I think dance is a particularly valuable art form for making visible what is often excluded, consciously and unconsciously from the act of self-definition that goes on when people imagine a community.

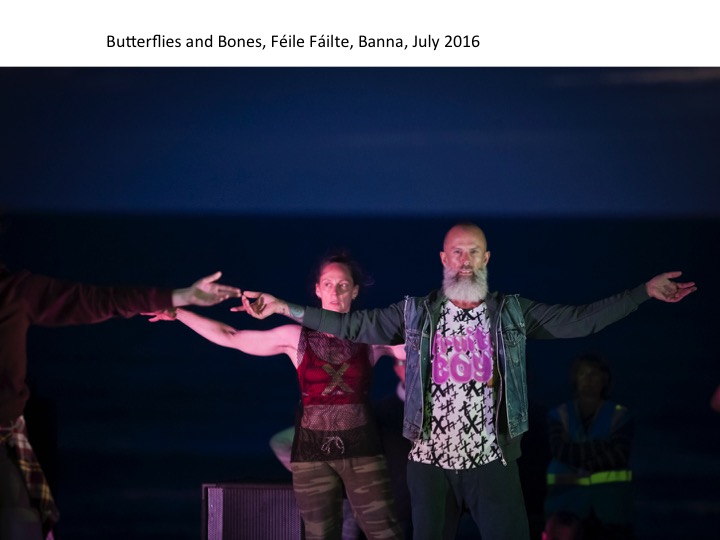

This impulse was very much behind the work of The Casement Project, the project that I led as a response to the Centenary Commemorations of the Easter Rising. Most of you will know that it was a multi-platform project that danced with the queer bones of Irish rebel, British knight and international humanitarian to imagine an Irish national body more hospitable to the stranger. It took place in academic symposia, in workshops, on stages, on screen and on Banna beach not far from here. I’m going to focus on Féile Fáilte for this last part of the talk to illustrate how artists might make and support community, in a way that makes visible prevailing exclusions in other versions of community and other definitions of who is allowed to be in public.

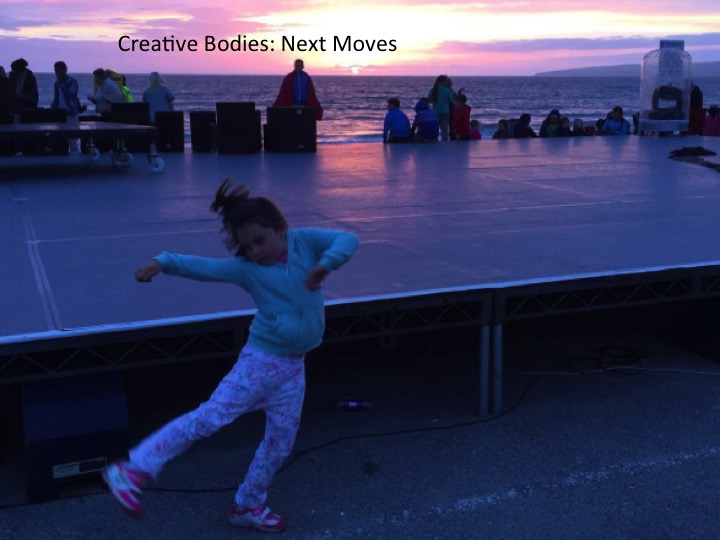

Féile Fáilte was a day of dance on Banna Beach. I chose Banna because it was where Casement had been captured on Good Friday 1916 on his way, to intervene in the Easter Rising. However the beach was important for a number of other reasons: when I was conceiving the project, the media was filled with images of migrants and refugees arriving on the beaches of southern Europe, landing there is they’d crossed safely, washed up there if they were tragically unlucky. The shoreline was the place where we, the European Community, were confronted by the complexity and needs of the other, an other, that as President Higgins often reminds us, was us, a queer and complex strangeness that Casement embodied also when he came ashore on Banna. More positively, I imagined the beach as a place where Irish people of all ages are a little more in touch with their bodies, bodies sometimes stripped to soak up the sun, other times wrapped but vigorously activated in bracing walks or adventurous surfing. The beach is a relatively democratic public space and for the kind of welcoming event I wanted to create, having a space where all kinds of people could feel comfortable was essential. But making a space where all kinds of people can gather required a careful choreography of people, resources and ideas. With The Casement Project team, I directed the resources of the State to literally making a platform on which different kinds of bodies could be visible.

We built a stage on Banna on which performers in wheelchairs could dance, (Croí Glan Integrated Dance Company), alongside Siamsa Tíre, and the multiethnic cast of Catherine Young’s beautiful Welcoming the Stranger that I commissioned for the event, a cast of local non-professional dancers some of whom are recent arrivals to the county and some who’ve been here all their lives.

We had Mangina Jones, former Alternative Miss Ireland as host, music from the brilliant Rusangano Family, dancing from John Scott’s IMDT and its diverse group of performers.

We had Mangina Jones, former Alternative Miss Ireland as host, music from the brilliant Rusangano Family, dancing from John Scott’s IMDT and its diverse group of performers.

We had a céilí and a pyro display.

We had a céilí and a pyro display.

The platform was built to be accessible, not only for wheelchairs, but in fact for anyone who was watching, so that when we had a disco or a céilí or enthusiastic audience participation during the Rusangano Family set, those that were watching could in a moment be dancing, crossing easily the border between stage and surroundings. The artists were the public and the public were the artists. It is the ability of people to move between spaces and not get trapped or fixed in defined locations that mattered to me in this choreography of an inclusive community.

The platform was built to be accessible, not only for wheelchairs, but in fact for anyone who was watching, so that when we had a disco or a céilí or enthusiastic audience participation during the Rusangano Family set, those that were watching could in a moment be dancing, crossing easily the border between stage and surroundings. The artists were the public and the public were the artists. It is the ability of people to move between spaces and not get trapped or fixed in defined locations that mattered to me in this choreography of an inclusive community.

We paid attention to some other kinds of invisible exclusion too by providing free transport from Tralee to Banna and back. I didn’t want owning a car to be a barrier to participation. Likewise we provided some resources for LGBT refugees that had marched for the first time in the 2016 Pride event in Dublin to travel to attend Féile Fáilte. It’s no point putting on a free event for everyone, if people can’t afford to get there to take up your apparent generosity. My sense of choreography includes not only the bodies on stage but the processes that make it possible for some bodies to show up, to be visible, to participate and others not. In this respect, choreography can teach a wider public about the resilient structures that enable a more inclusive experience of community and public.

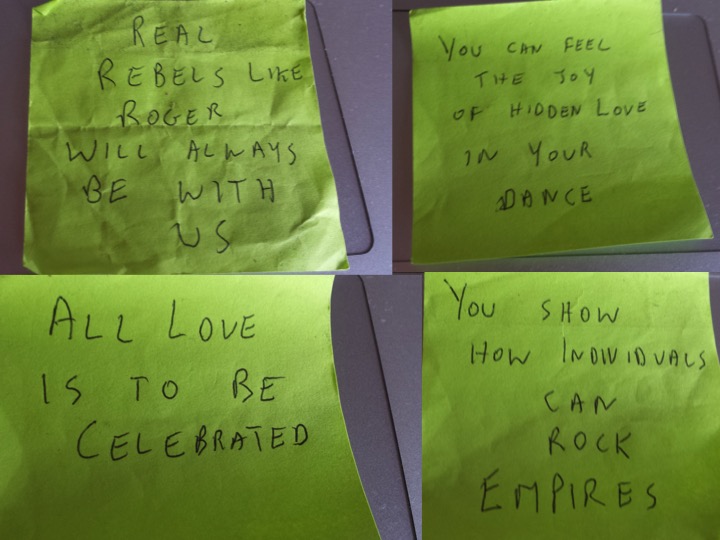

But to make a space for inclusion, means risking an encounter with what is unfamiliar and strange and that experience isn’t always comfortable. Many of you will know that despite the overwhelmingly positive response to Féile Fáilte, where people described it as a utopia and asked that we do it again, there was a letter of complaint from a Tralee family to the local radio in particular about the content of my work Butterflies and Bones that referred to Casement’s sexual life. It being July and in the absence of much else to talk about, there was a brief storm of outrage on local radio and paper with a counsellor in Cork who hadn’t been to the event complaining that we had disrespected Casement and his family by referring to what he did with his body and how his body was treated after his death. Some of the people who complained said the event was not family friendly, which I found odd since my biological and chosen family were happily in attendance and I resented the attempt to take family away from us, to exclude us from the notion of family. We were still in the wake of the Marriage Equality Referendum where some of the arguments against marriage equality were advanced on the grounds that gays and lesbians shouldn’t be allowed to have families – ‘Don’t let same sex couples raise children’, as Danny Healy Rae told Hot Press magazine. (Happily for me, Kerry constituencies voted for 55% in favour marriage equality, solidly average between Dublin’s 72% and Roscommon’s 48% for and 51% against). One person interviewed on the radio said my work would be fine on a side stage but it didn’t belong in the middle with everyone else, ‘it’s not general entertainment’. Féile Fáilte was precisely a choreography to resist that exclusive, marginalising version of community and though it was hurtful to hear some of the challenge to that vision I was trying to perform on Banna, the reality is that the challenge of inclusion, of a public space and community that shelters difference, is one that applies to me as well as to those who are challenged by the work I present. This recognition of the public as a space where dissensus and disagreement can be safely held together seems particularly important in fractured societies such as America divided on Trump, Britain on Brexit, and Ireland about to deal with its legacy of bitter Civil War.

And the point of Féile Fáilte is that it worked – even those people who complained about Butterflies and Bones hung around to be offended and to watch the pyro display at the end. We shared Banna together without violence and disruption. And they lost nothing by hanging around because the event was free to attend and people were free to leave whenever they wanted. So when we think of choreographing community, I think it’s worth thinking about the structures that allow differences to coexist, for the surprise, the delight and the challenge of strangeness to be encountered. (The Irish phrase, trín a chéile, literally through one another, has a sense of losing one’s usual composure, of being lost to ones familiar self). And sometimes as artists, we are that strangeness to others, perhaps because we are willing to be strange to ourselves And sometimes the encounter with others confronts us with their resistant but instructive otherness. And in this encounter we are interdependent, not independent.

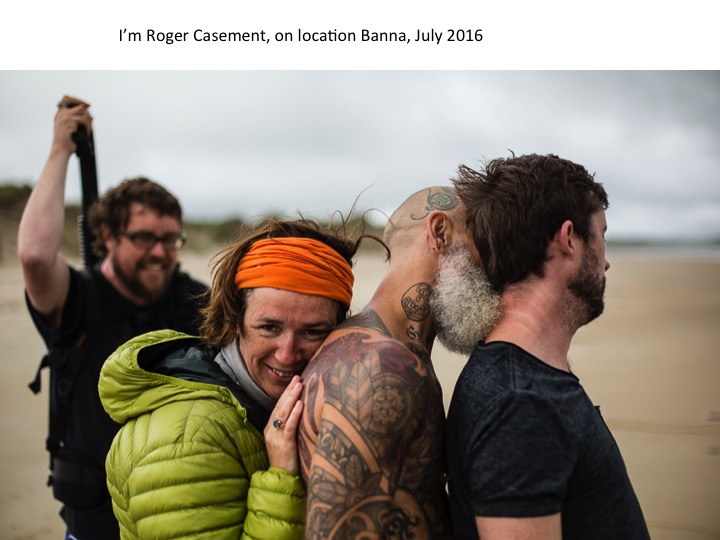

So if I return to the photograph with which I started, which shows me dancing on Banna I want to conclude by revealing it not as an example of my solitary independence but as an image born of interdependence. The image is of my dancing on Banna as part of the filming of I’m Roger Casement the dance film we made as part of The Casement Project.  Not only does the image depend on the presence of the photographer, (Mickey Kelly) but there’s a whole film crew recording while that image is being taken, and the cast of performers sheltering in the dunes until they dance again.

Not only does the image depend on the presence of the photographer, (Mickey Kelly) but there’s a whole film crew recording while that image is being taken, and the cast of performers sheltering in the dunes until they dance again.

More importantly, that material that I’m dancing is generated through others. I was never supposed to be dancing in the film, but Theo Clinkard with whom I developed the material wasn’t able to join us for the performances so I took his part. Some of the material that I ended up dancing on Banna derived from a solo I’d made in China in 2007. Aoife McAtamney learned and transformed that solo as part of our research for The Casement Project and her material was passed on and transformed again by the other performers in Butterflies and Bones. I eventually took it back into my own body when I danced Theo’s part on Banna. That journey of through otherness, of interdependence is all present for me in that image. But it’s not only an interdependence on other humans. That dancing was dependent on the weather, on the sea, on the sand under my feet. The image is here because of the mediating technology of the camera, still and film, my movement on Banna directed towards the fixed and particular frame. As we consider our interdependence, it is a future of complex connections that we need to take into account.