Isabella and I are happy to be able to draw on the resources of an Arts Council Project Award to continue the work of Tearmann Aiteach/ Queer Sanctuary and the investment of time, energy, imagination and relationships that have already made the practice such a resonant and positive experience for me. The Project Award is especially welcome in that it allows us to pay collaborators for their investment in the work but at just under €50,000, the award is not so big that we don’t also rely on the generosity of other supports such as Dance Cork Firkin Crane’s Ceist Residency.

Isabella and I are happy to be able to draw on the resources of an Arts Council Project Award to continue the work of Tearmann Aiteach/ Queer Sanctuary and the investment of time, energy, imagination and relationships that have already made the practice such a resonant and positive experience for me. The Project Award is especially welcome in that it allows us to pay collaborators for their investment in the work but at just under €50,000, the award is not so big that we don’t also rely on the generosity of other supports such as Dance Cork Firkin Crane’s Ceist Residency.

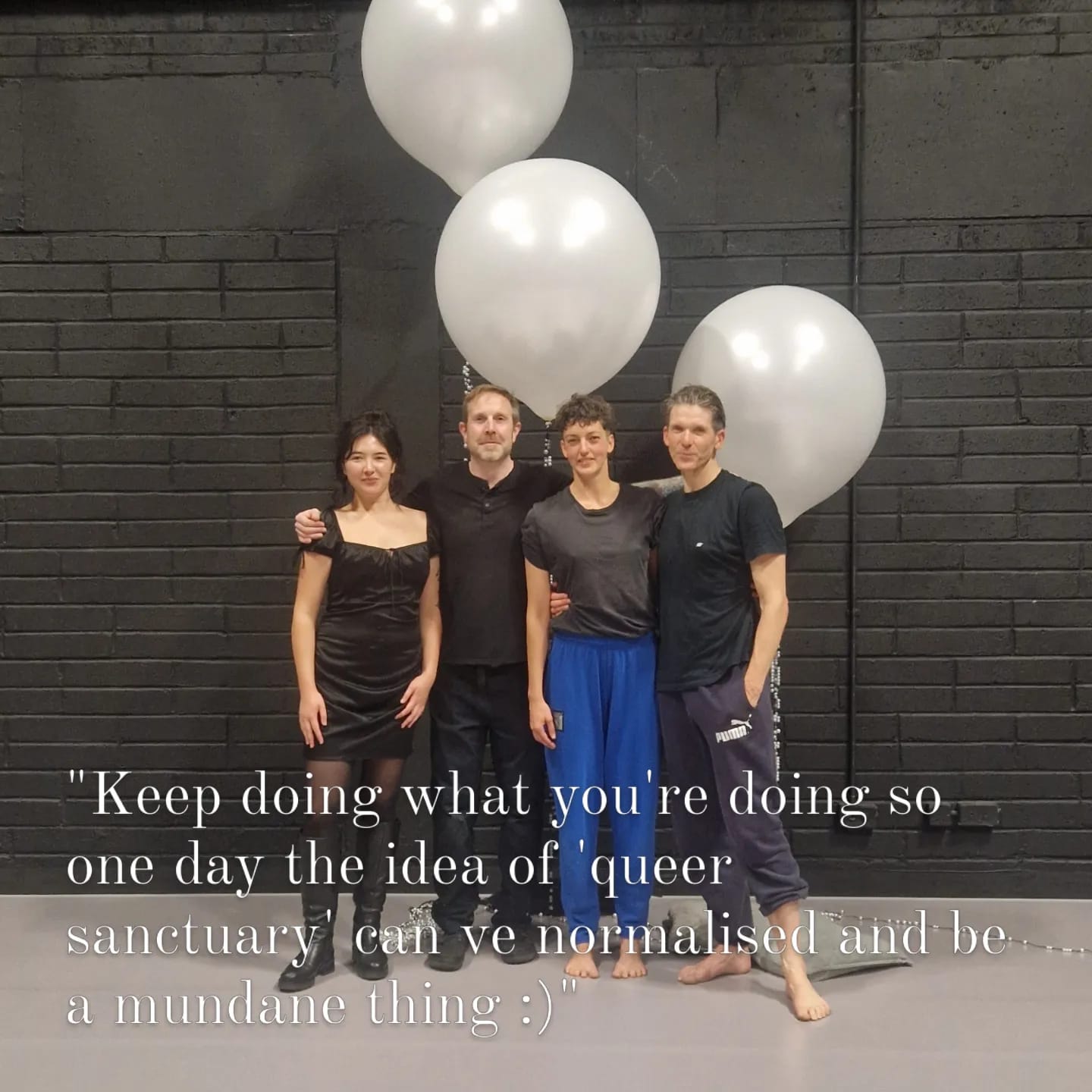

Thanks to the residency, Isabella and I spent a week in March at DCFC reconnecting with movement practice and exploring how our choreographic structure could evolve for the new performance we’re making. The residency gave us time together to connect remotely with our collaborators, like theatre maker and designer Choy Ping Ní Chléirigh Ng. Ping will be creating a digitally enhanced performance space that resonates with the invisible energies of the dancing and provides ways for audiences to witness and/or enter into the dancing sanctuary. And because we’re attentive to care and pleasure in our practice, we also used the time for doing the planning, admin and logistics that we freelance artists so often do outside of “working time” as if that labour wasn’t of a piece with the creative work at hand. Being able to do all of the work in a similar space has helped me to make sure for myself that the approaches and values we’re hoping to embody in the dancing are present equally in our admin and planning; and equally that the care and energy invested in logistics and planning by us and by our producer Louisa, is recognised as part of our sanctuary making practice.

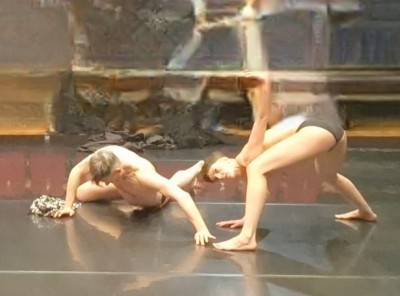

As part of the Ceist Residency, we (mostly Isabella) taught class on the Thursday of our week in Cork. We’ve been talking for a while about how we invite others into the space of sanctuary. We know this version of a space for flourishing has evolved to respond to our needs, desires, pleasures, and though queer, as cis, white, able-bodied Europeans we know that our perspectives will not be shared by all, not even by all who share the appetite for queering. We’ve already experienced what it is to invite others in as collaborators in advance and as audience in the moment of performance. Sharing our practice through class was a different way to introduce people with varying movement backgrounds (improvisers from Japan, modern dance teacher for seniors from the US, circus artists, contemporary and classical dance professionals and enthusiasts) into the way of working we find generative for us. Isabella led the warm up with energy/qi cultivation work. She and I don’t usually do the same warm up together. We’re not trying to create a sameness in our bodies. But we do warm up alongside one another (I’m usually doing yoga or a Cunningham-based warm up) in a way that allows us to attune to sharing the space and the resonances between us while maintaining an independent track. This is parallel play.

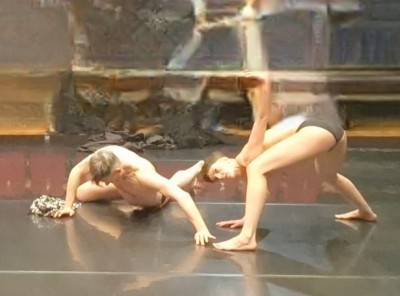

For the class, Isabella’s energy cultivation work brought the group to a state where we could dance our individual movement paths alongside one another, eventually coalescing into an improvisation guided by the lightest of touch between bodies, a dance inspired by what we think of as particles in our TA/QS structure. (I think the idea of particles is one that originated for me- I’m not writing for Isabella – in work Daniel Abreu shared during our Dancing More Wisely research at DCFC and which grew as partner work in another phase of Dancing More Wisely with Wanjiru Kamuyu.). Some of the feedback at the end of the class mentioned how gently and comfortably the group had been brought into contact, recognising that sometimes in a class situation, contact is expected without prior negotiation. And it was also important for us that though the class moved towards contact, that contact could be safely avoided or acknowledged at a distance rather than assumed and required. This kind of feedback working with others was very useful for us as we consider if and how to engage audiences and others in our dancing structure.

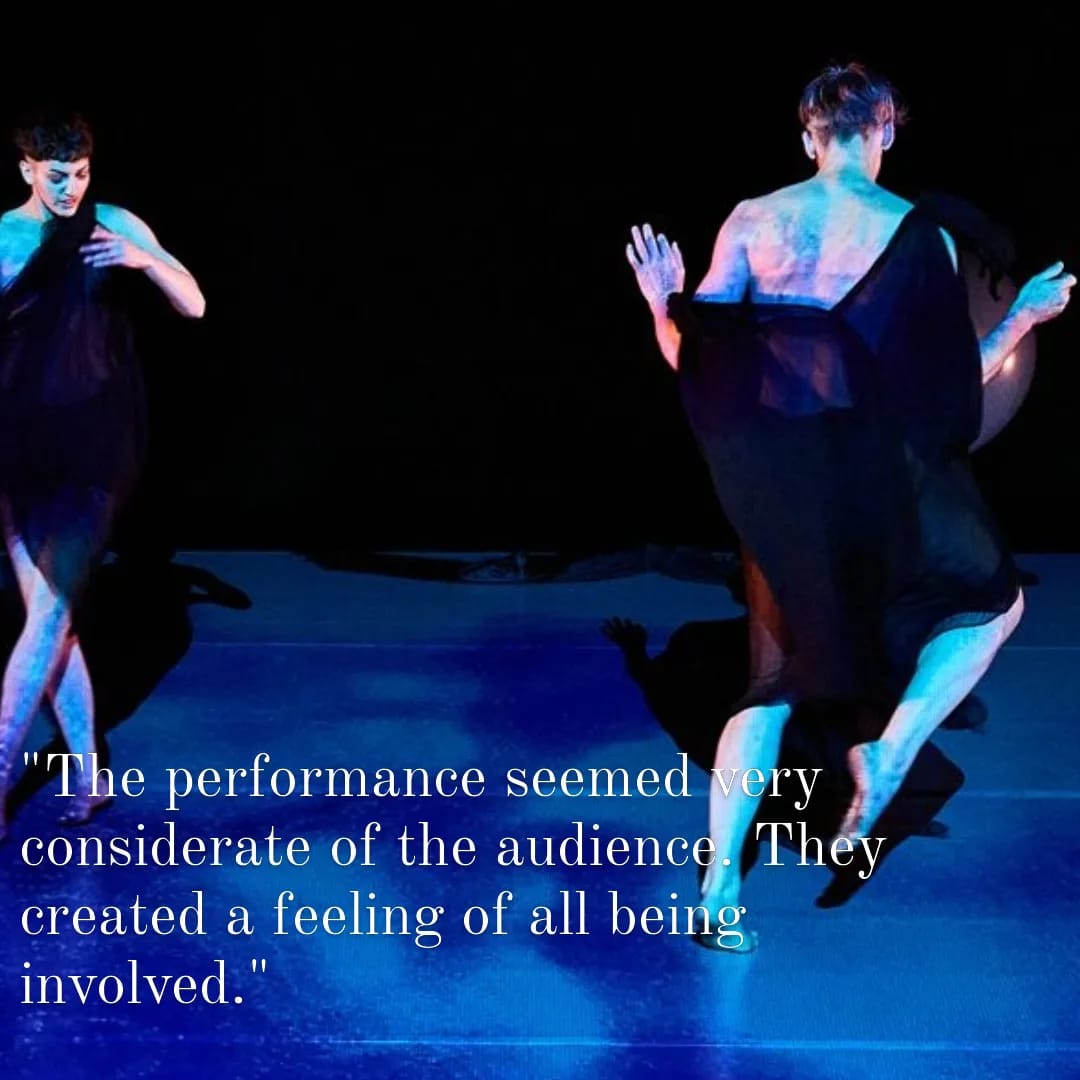

The Ceist Residency also includes an opportunity to share some ideas or work in progress with a small gathering of interested people. Having danced in progress versions of our structure in other settings, it felt less important for us to perform for this sharing than it was to use the opportunity of having a public to experiment some more with inviting viewers into movement with us. There’s no better way to find out how to do something like that than to try it. We built upon moments in our existing structure where we ask the audience to look after our string of pearls before retreiving them later to measure the space and our relationships in it. For the sharing, we offered the pearls to audience members to hold with us (some declined and chose to hold the pearls in their seat instead) and move with us into the performing space. Knowing that some of the audience members were people who had attended our class the day before gave us some confidence that people would trust us and themselves to navigate the invitation. When they were comfortable in the space, we asked them to rest there with the pearls while we danced some more. Some chose to leave the space and some stayed creating an architecture, energy and attention that we couldn’t on our own. And perhaps they suggested that this work could be experienced from different places, inside, outside, passing between, feeling inside from the outside, feeling outside from inside. We end the dancing with a movement inspired by the gestures of cardinal points that we use in our structure to re-establish simpler forms in our plural and transforming world,

It felt very positive to share the space with others. It was encouraging to hear that our openness as soon as people arrived into the studio created a space that felt welcoming and safe to participate in. Some people speculated if that would have been the same for an audience with fewer dance practitioners and enthusiasts. Certainly it was reassurance for us that having done the class the previous day, we weren’t inviting complete strangers into our sanctuary. And it’s helped us consider what kind of preparation for us and others it takes to create the sanctuary “outside” (but like Derrida’s parergon, a frame that is extra to but essential to what it contains) of the dancing/performance. It is precisely this perverse crossing of inside and outside that makes this a work of queer sanctuary.

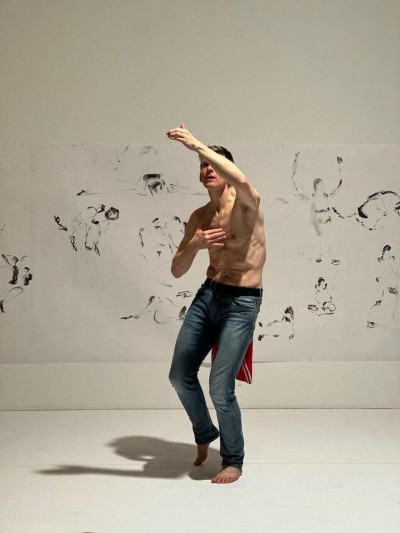

One other reflection for us, as we prioritised looking after the guests we invited into TA/QS was the cost to us and our desire in the moment. We didn’t want to invite people in and abandon them as we went off to our play. But in making sure they were alright and understood what the parameters might be, we set aside all but the briefest moments of our dancing – though we we could dance them with those newer people in the space, the experience was positive. I think we’re still working out for ourselves what the balance of care for others and care for ourselves looks like. It’s an aesthetic and ethical enquiry that has continued resonance for me as I refocus attention on what I want for myself and my own creative work, given I also value the work of facilitation that creates positive spaces with and for others. Working with Isabella has helped me find an enriching dancing space of mutual support and joyful freedom. The opportunity we’re embracing now is to find out who else would enjoy expanding that space with us.

Thanks to Jenny Traynor who helped Isabella and me to put together our Project Award application.