As I start to think about Cure for next year, John Waters article on the stabbings that happened at a concert in the Phoenix Park on the 7th July caught my attention as it interprets in the particular event symptoms of a greater cultural malaise. 9 people were hurt during a concert featuring Snoop Dogg, Calvin Harris, Tinie Tempah and Swedish House Mafia.

You can read more about the events in this here

Catholic Archbishop Diarmuid Martin has blamed the “culture of violence and . . . the emptiness of a culture of drink” and other politicians have discussed restrictions on alcohol advertising in the wake of the Phoenix Park stabbings. Waters article examines what alcohol might be setting free:

The Irish Times – Friday, July 13, 2012

We need to understand the rage in our midst

Last weekend’s Phoenix Park stabbings were a vivid manifestation of the rage that now defines our culture, writes JOHN WATERS

VIRTUALLY ALL the reporting and analysis of last weekend’s events in the Phoenix Park have been brought to us by unshockable crime correspondents and unreconstructed rock critics.

Predictably, then, we have heard a great deal about, on the one hand, the security and law-and-order dimensions, and, on the other, the particularities of electronic dance music and the putatively violent context of the attendant dance culture.

We need to dig deeper. About three years ago I suggested here that what we were calling the “economic crisis” was something far worse: an anthropological calamity arising from a misunderstanding of desire.

Having invested all hopes in the balloon-basket of materialism, (which had recently fallen out of the sky) we had being brought face-to-face with a confusion centred on an inability to define what we want.

What we skirt over as “materialism” denotes a core cultural misunderstanding that reduces human expectations to what is tangible and comprehensible. It is symptomatic of a culture that has lost its sense of the mysterious meaning of reality, and must therefore offer three-dimensional bait to keep the human mechanism ticking-over.

At the heart of such a culture is a hole, from which rage emanates in the manner of lava. What emerged in the Phoenix Park last Saturday was an especially vivid manifestation of the rage that now defines our culture.

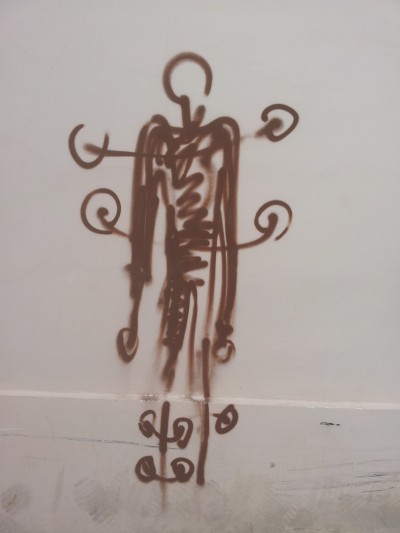

We have come to think of a “stabbing” as exhibiting a narrow meaning related to the individual wielding the knife. More than 20 years ago Robert Bly wrote in Iron John about the power and meanings of knives. He recalled that, in traditional societies over many millennia, knives were used in the initiation of young men. The community elders would take the initiate into the wilderness and subject him to a regime of trial and fasting lasting several days.

Around the campfire, the boy would hear the great myths and stories that men shared only among themselves. On the third night, the elders would pass around a bowl and, one by one, would cut their arms with a knife and bleed into it. When the bowl reached the boy, he drank the elders’ blood.

Nowadays we shudder and dismiss such rituals as backward and barbarous, but neglect to take account of the barbarisms that occur in our midst because we no longer honour the natures of men. The elimination from our culture of the teaching, benign-authoritarian father has left us with generations of young men who, as Bly observed, are “numb in the region of the heart”. Because young men are never allowed to come away from their mothers, they stand on the threshold of manhood but cannot enter.

The umbilical cord has been severed, but little more. Still tied to their mothers’ apron strings, more and more of our young men carry knives to announce their manhood. With their fathers cast into silence, they are starved of the wisdoms and mythologies that might sustain a healthy male existence. In our obsession with minoritarianism, we have overlooked some of the most vital constituents of a healthy community.

Adrift in the numbness that engulfs them, many of our young men now walk with an outward appearance of normality but inwardly lurch uncontrollably – from, for example, a learned piety to intense rage – all the time seeking something to provide some illusion of feeling while simultaneously keeping the numbness at bay. Sometimes the cultural conditions cause their defences to break down and another calamity ensues.

The great pioneer sociologists believed that, when understanding social deviance, it is erroneous to focus solely on individual wrongdoing. When someone commits some act that scandalises society, they believed, he or she is, in part at least, acting out some repressed, unacknowledged sentiment of the tribe. This understanding is supported by the coherence of certain dark statistics – murder, suicide, addiction – which tend to follow unique and consistent patterns within a given society, year on year.

A century ago the French sociologist Emile Durkheim argued that communities are psychic beings, with distinctive ways of thinking and feeling. The suicidal individual’s sadness, he wrote in On Suicide, comes not from “this or that incident in his life, but from the group to which he belongs”.

He also diagnosed a condition he called “anomie”, resulting from circumstances whereby the normative regulation of societal relationships by rules and values has collapsed and caused individual feelings of despair, isolation and meaninglessness to erupt as individual pathologies and civic disorders. He defined the underlying collective condition as “the malady of infinite aspiration” – wanting more and more of what has already failed to satisfy.

In due course, those responsible for the Phoenix Park stabbings will be paraded before us on their way into court. We will shake our heads and arrive at some narrow moralistic conclusion, in accordance with which the culprits will be sentenced.

But if, as a society, we fail to see that it is we who made these young men what they are, we will have lost another opportunity to understand what has been happening to us. It is at least as mindless as what happened last weekend to talk of “testosterone-fuelled thugs” gone mad in the park.