Today we brought Porous from the studio in Donegall St, Belfast to the Writer’s Square nearby. Porous is a 20 minute piece I’ve been invited to make for Maiden Voyage as part of their Dance Exposed series that brings dance into public spaces. It will premiere officially in the Belfast Festival this weekend, with three performances on Saturday in the gallery space at the MAC and three further performances on Sunday in the foyer of the Ulster Museum.

Today we brought Porous from the studio in Donegall St, Belfast to the Writer’s Square nearby. Porous is a 20 minute piece I’ve been invited to make for Maiden Voyage as part of their Dance Exposed series that brings dance into public spaces. It will premiere officially in the Belfast Festival this weekend, with three performances on Saturday in the gallery space at the MAC and three further performances on Sunday in the foyer of the Ulster Museum.

I don’t often do commissions and I was curious to know what prompted Nicola Curry, Artistic Director of Maiden Voyage to invite me to make a piece for the company. I think my experience of working in public space, on bodies and buildings, was part of the attraction. However I was concerned that I would have to work with a group of dancers I didn’t know and manufacture a piece in two weeks just before the show. I have no doubt I could do that, but I’m not sure that the resulting work would connect with or develop the kind of choreographic process I’m happy to have been involved in recently. Fortunately, Nicola was very accommodating, so instead of making the piece in a couple of weeks before the premiere, I arranged for us to work during the summer, with a further week of rehearsal just before the opening. By having that time in the summer, I felt that I could get to know the dancers, experiment and take risks trying out different things, without the immediate and often suffocating pressure of an imminent deadline ( a pressure that would compromise my openness and that of the performers). I knew that whatever we did in the summer, I could always set the experiments aside and return to safe ground in October if necessary. I found that freedom very positive as Vasiliki, Carmen, Oona and I worked in the sunshine in studios that are a bike-ride away from my home in Walthamstow.

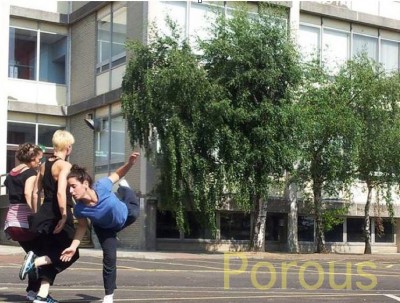

Though Nicola talked about the commission for Dance Exposed being site-specific, I understood that the work would travel to different sites and therefore needed to be more site-responsive. That responsiveness needed to be in the structure of the work but also in the way the performers would inhabit the choreography and the space. I enjoyed generating with them material for an improvisation and approaches to that improvisation that would guide, connect and free them. I wanted them to be porous to their own sensations, to the interaction inside the trio, and to the environment in which their structure was unfolding. The multi-dimensional task was not easy, but as we draw closer to the premiere, I am very happy to see their increasing skill in navigating the task, individually and together. I am delighted by the surprises that emerge from this now familiar structure and material.

Already in the summer, we took the rehearsals out of the studio, to make sure that the dancers could experience sensations beyond the confines and familiarity of white walls. Today Porous made sense to me in Writer’s Square. It seemed to belong, despite its idiosyncratic movement language. Passers-by could wander through the trio without destroying it, because the choreographic structure could already accommodate that different energy. Its boundaries are permeable, not defined by footlights or proscenium arch. Even a group of stoned teenagers who initially threatened to disrupt the choreography gradually became enfolded in it, one young woman standing close to watch the dancers while the others sat on a wall to observe. I was alert, wondering if I needed to protect the dancers, but I’m glad that they found a way to be in the work without shutting off or out the encroaching energy.

This structure I have made with them owes much to what I’ve learned from the Cure choreographers and I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to transform the things I’ve learned for a group of dancers that I haven’t known as long or deeply as I have those with whom I normally work. I’m very curious now to see how audiences will respond.