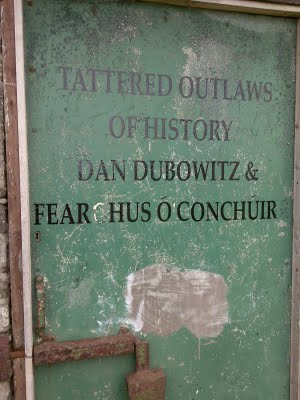

To mark Heritage week and to see the ending of the Tattered Outlaws installation, Caroline Cowley invited me back to speak about how Dan and I made the piece.

I’m used to trusting my work to performers to give it life but it was strange and delightful to see how the installation, not a live performance, has developed since we left in July. I notice the visitors’ book damp from its time in the tower, a ‘G’ wiped off the lettering on the door, an extra lamp from the home of one of the invigilators added to make the space more friendly.

Those invigilators have been a huge asset, heaving in and out the generator, nimbly negotiating the planks to remove the protective plastic bags from the screens and helping visitors to understand the installation. Seeing how they invested in the piece, committing time, energy and creativity to making it possible, has been an inspiration. I see the work which Dan and I made grow through them and through the visitors who have engaged with the work. This growth is not ancillary to the work. It is a fleshing out of potential inherent in the piece, but potential that is unrealised in many works of art that don’t find the right context.

It is impossible to determine what the outcome of the work has been but if nothing else it has been an occasion for connections to be re-established, not only between these towers, but also between people:

When Senator Fergal Quinn spoke today about how his father built the Red Island holiday camp that incorporated the Skerries tower, he mentioned in passing the last caretaker who lived in the building grafted at that time on to the tower. As it turned out, the widow and daughter of the caretaker were in the audience and proud to reconnect their personal history of the tower with a bigger narrative.

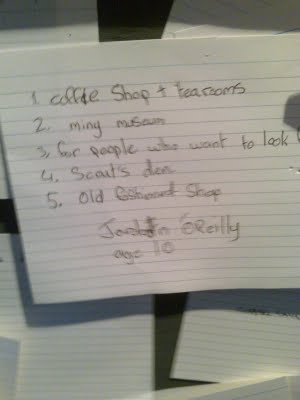

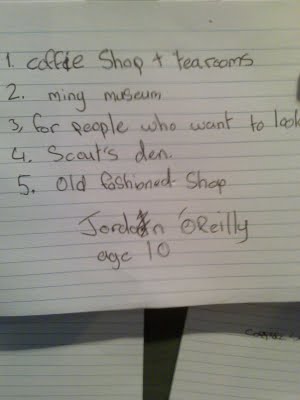

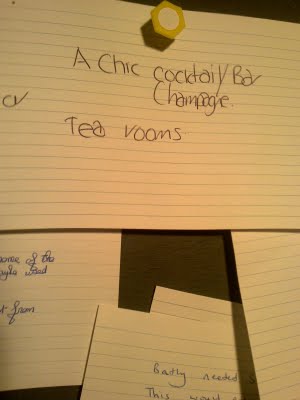

The board we left with the question ‘What next?’ is covered in suggestions about what the tower could be used for (a scout hut, a museum, a swimming pool, a chic wine bar…). The board prompted someone from DIT to suggest that the tower could be used as a live project for his architecture students. They propose to do feasability studies on a number of ideas that the public have contributed and so the work continues.

All of which prompts me to ask, not in a masochistic way, whether the connections and creativity that has issued from the project needed our work at all? Would it have been just as effective to open the tower and maybe put some historical material about the towers inside?

But I think that, more than a historical account of the towers, our work sanctions and invites the personal response to these buildings that liberates people from feeling they have to be experts to contribute. All kinds of responses, no matter how idiosyncratic, are given shelter within the structure that Tattered Outlaws creates: the woman who described her tomboy derring do playing inside the tower is already in the performances of Zach and Eva (and Bernadette and me); Fergal Quinn’s account of dressing in a sheet to stand on the roof on the Skerries’ Tower to play the part of the Banshee whom the conga line of dancers from the holiday camp would serenade at the end of the night, is somehow connected to the ghost performances of mine on the roofs and to the lines of visitors that snake out the door to see Tattered Outlaws. The piece anticipates and welcomes all the memories that visitors have brought.

Tattered Outlaws honours the individual while providing a context for that individuality to connect to others. And it gives expression – incarnation – to the stuff that people don’t articulate in words: it remembers those that have passed away, and reminds us of our inevitable passing.

Post a Comment