Michael Seaver wrote an article in the Irish Times about nudity/nakedness in dance and asked me to contribute to it alongside Aoife McAtamney and Nina Vallon, and Fitzgerald and Stapleton. The variety of perspectives is instructive: gender plays a part in how nakedness is received, though the different approaches of Aoife and Nina and of Áine and Emma suggests its not just about gender. Reflecting on the article and the work of the artists involved, I think female nudity is more readily commodified (‘lads’ mag’, artistic muse)and can therefore be less remarkable than male nakedness. However, female nakedness is even more challenging than male nudity when it refuses to conform to the conventions of commodification in the way that Fitzgerald and Stapleton definitely enact in their work.

Though he understandably didn’t include all of my responses in the article, Michael asked me some thought-provoking questions. Below are the questions and my responses

1. What has been the impulse to present a nude body onstage in your work? Where did that decision come from?

I wouldn’t say I have an impulse to present nudity on stage. I don’t give much thought to nudity. I don’t give much thought to tendu or

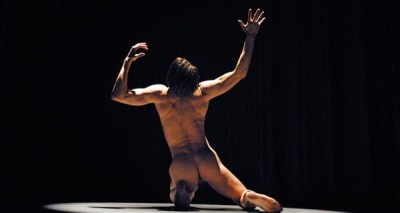

turn either but they’re often in the choreography as a means to an end. Nudity is a tricky notion anyway. You’ll already know Kenneth Clark’s distinction between the (aesthetically acceptable and supposedly not titillating) nude and the rawness of the naked. I think that nakedness emerges in some of my work because I’m not afraid of it. If it seems necessary or useful in the pursuit of a choreographic idea then I’ll follow it. So for example in Tabernacle, Matthew was naked near the beginning of the piece. That material came about because I’d asked the dancers in rehearsal to think about what they wanted to leave behind and Matthew had an idea of shedding skin and he undressed laying out his clothes like shed skin on the ground. I never ask the performers in my work to be naked. They offer it as part of an idea if it makes sense to them. Equally, if I’m performing, as I am in Cure, I’ll offer nakedness if it makes sense to me. So in one section where the intimate relationship between a piece of fabric and my skin is important, it made sense to me to take away all the other barriers – clothes – between me and that fabric. The result is nakedness but it’s not the aim.

2. In what way(s) can nudity be artistically meaningful?

When we were making Mo Mhórchoir Féin for the RTÉ Dance on the Box series, there was some question about how my near nakedness in a church would be received. It was suggested that I wear something else, maybe even a flesh-coloured body suit. Those options made no sense to me since the vulnerability of the naked body was important to the impact of the work, as was its implied sexuality. More importantly, the near-naked body of the male dancer in the church has a central and overwhelmingly authoritative precedent in the space already – the figure on the cross. So in that case, the unclothed body was a necessity. It wouldn’t make sense otherwise.

3. Can you relate nudity to your overall artist vision for Cure?

The physical nakedness in parts of Cure might be related to a willingness to be bare, to be open, to show things as they are rather than hide. I think the choreographers who’ve contributed to the making of Cure all have that impulse to honesty and openness that makes them great performers and artists and they’ve each found ways to reveal and lay bare what they think matters about cure. And in some instances, that laying bare is literal, not because they required it of me, but that their idea was best expressed by being naked.

4. How does it feel different performing nude than clothed?

If the choice is right – the right clothes, the right nakedness – then it’s not where my attention is in the performance. If the clothes or nakedness make me self-conscious then they’re the wrong choice. I performed the solo from Cosán Dearg in the middle of a busy art gallery in Beijing with lots of people taking photos on their mobile phones but the nakedness for the solo was right and so I didn’t feel exposed or vulnerable in that was potentially a weird situation.

5. How soon in your creative process to you think about costume?

The sooner the clothes are integrated the better. (Though I’m not as organised as Raimund Hoghe whom I heard has the dancers costumed before starting rehearsals and I can see how that makes sense) How we move is altered by the textures on our body, the tightness or freedom of a cut, or by the sensitivity of exposed skin. It doesn’t make sense to practise and practise movement material and not practise as sensitively the way that clothing or nakedness impacts on that movement. It’s not that it’s always about selecting clothes that are free: maybe one wants a particular restriction. In Cure, I wear shoes for some parts and that changes my relationship with the floor. It makes some movements easier because the shoe protects my feet but it changes others, like turns. But if executing a perfect turn was the objective then we’d make a different costume choice. For Cure, that’s not the objective! So no last minute trips to Penney’s – the clothes will be as familiar and worn in as the movement.

Post a Comment