Below is the text I wrote to prepare for my presentation for the stimulating Theatre of Change Symposium organised by The Abbey Theatre and curated by Fiach MacConghail and Dominic Campbell. I didn’t read it so the video documentation will probably show how I deviated from the plan. However I didn’t want to spend my first opportunity to be on the Abbey stage reading and risked riffing on this prepared text instead:

The Casement Project

If you were to create a new State today what would your concerns be?

Tá an áthas orm bheith anseo inniu. Ní ró-mhinic a bhíonn córagrafadóir comhaimseartha ar an árdán anseo agus táim an bhuíoch le Amharclann na Mainistreach, le Fiach agus le Dominic as ucht an gcuireadh labhairt libh.

Photo Ste Murray www.ste.ie

I’m very happy to be here today. Choreographers of contemporary dance are not visible on this stage particularly often, and so I’m grateful to the Abbey, to Fiach and particularly to Dominic for the invitation to speak to you.

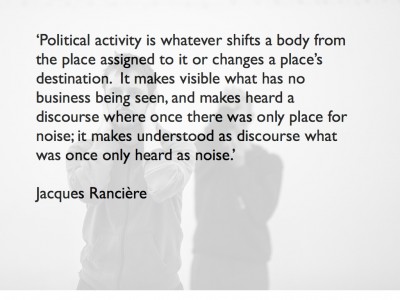

For French philosopher, Jacques Rancière

Photo Ste Murray www.ste.ie

What appeals to me in this formulation is the choreography it implies. It’s about moving bodies from one place to another, making visible what hasn’t been seen and giving expression and form to what was previously unintelligible. It reminds me that of the choreography in political, social, economic, ideological structures, what Ranciere would calls the police, assigning particular movements, particular places, refusing to acknowledge some bodies at all. And it bolsters my commitment to dance as a form of knowledge to help question, analyse, imagine and embody other possibilities than the ones we’ve been given.

When I think about creating a new State today, I think about what new choreography could a national body perform and how hospitable to a diversity of individual bodies, movements and expressions that collective choreography could be. And I want to propose the importance of dance in this new state to help us question, analyse, imagine and embody what that new choreography could be and how that choreography will continue to evolve.

Despite our reputation as an articulate nation, capable of creative, subversive and resistant dexterity in the way we use language, I don’t think we’ve recognised, explored or embraced a similar articulacy in our bodies. And that lack of physical fluency, historically and today, has a negative impact on individual bodies but also prevents us from imagining new possibilities for our collective choreography.

Photo Ste Murray www.ste.ie

I speak of the importance of dance with the zeal of a late convert. I didn’t start training professionally until the of 23 having read English at Oxford and done an MPhil there in European Literature. I am someone who has a huge respect for our literary heritage but t was studying Yeats Noh plays, Beckett’s austere choreographies and eventually Friel in Dancing at Lughnasa that I recognised in them that there were moments in their dramatic work when language had to give way to bodies and to movement. ‘Dancing as language had surrendered to movement, as if this ritual, this wordless ceremony were now the only way to communicate.’ As if…

There are historical explanations for our blindspots around the body: the colonial characterisation of the Irish as untamed, wild, violent and ape-like provided a justification for civilising colonial rule. Little wonder then that cultural and eventually political nationalists wanted to present the Irish body as one that could be self-controlled, making an alliance with Catholicism as a way of inculcating respectable, moral physical behaviour. However that conception of the acceptable bodies results at the foundation of the state in a Constitution that fixes women to the domestic environment, cherished as mothers, but denied autonomy of their own bodies. It results in a system which interns or expels those bodies which do not conform, whether they are bodies that procreate outside of wedlock (Magdalen Laundries), bodies that are poor (industrial schools), bodies whose desire for other bodies is not sanctioned (LGBT) , or bodies whose nomadism doesn’t fit the official state choreography (travellers).

Of course things have changed. After the Marriage Equality referendum, the state congratulates itself on its inclusiveness but I think it’s worth remembering that for the referendum to be carried, we needed to focus the campaign on love and avoid discussions of sex. What bodies want, how they interact is still a tricky subject to consider. There’s still work to be done….

And it’s not only about getting bodies moving. Ireland’s embrace of the global market means that what we need now is a skilled, resilient but above all mobile Irish body that can travel the world in search of employment. It’s no surprise that Riverdance’s disciplined army of sexy Irish dancers was the most prominent export of the Celtic Tiger exuberance. And it’s no surprise that Heartbeat of Home emerged during our more recent economic difficulties, with its cast of Irish dancers drawn from the Irish diaspora to remind the world what a strong, capable, globally connected body the Irish body can be. I don’t mention Riverdance or Heartbeat of home as a criticism but as a reminder to myself how easily choreography can be co-opted by the market and by a state desperately trying to be viable in that global economy.

What’s needed isn’t one more choreographer, but a choreographic creativity that checks what rhythms have become stuck, what movements deadened by habit, what bodies that are not being seen

Photo Aedan Kelly

Over the years, I’ve been using my choreographic practice to make my own small shifts, who knows how successfully. In

Match, a duet that takes place on Croke Park, I wanted to communicate to the wide audience that its broadcast on RTÉ allowed, that they already knew how to read emotionally and psychologically charged physicality. They watch it in sport all the time. However, as a dancer, I take the GAA DNA I’ve inherited (from my mother, uncles, shared with my brothers, sisters and GAA-star cousins like Cork Ladies footballer, Annie Walsh!) and shift its purpose, expand its possibilities to include me it. Of honouring an inheritance but shifting it to other ends.

In Mo Mhórchoir Féin, another film for RTÉ made in 2010 after the Ferns report and Irish Child Abuse Commission Ryan report, I put a male body dancing in a church alongside an altar boy and an older woman watching. Many people asked me about whether I intended to be iconoclastic by placing an almost naked body in the church but I reminded them that there has always been a semi-naked male body at the centre of Christian churches. It’s just we’ve forgotten how to see that physicality. So in my work, finding new choreographic possibilities for bodies isn’t only about invention. It’s about examining and releasing suppressed, ignored or forgotten potential in the existing body politic.

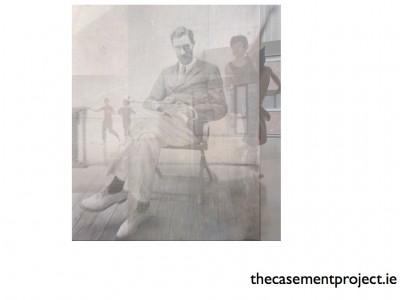

Original Casement image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

It’s for that reason that as part of the Arts Council’s National Commissions for 2016, and as part of the 1418now WW1 Centenary Commissions, I’m choreographing a work called The Casement Project that dances with the queer body of British peer, Irish rebel and international humanitarian Roger Casement. For those that might not know, Casement was born in Sandicove and came to prominence when, as part of the British consular service he published a report detailing human rights abuses and exploitation of the local population in the rubber trade in the Congo Free State. He was active with others in setting up the Congo Reform Association and was sent by the British government to report on similar abuses in the rubber trade in the Amazon, a report for which he was reluctantly knighted. Casement’s recognised in Ireland, particularly in the poverty of the West of Ireland which he also tried to alleviate, a colonialism related to what he’d witnessed in Africa and South America. He became increasingly involved in cultural and then political nationalism, raising money to arm the Irish Volunteers and eventually going to Germany in the First World War to secure arms and support for Irish independence. The British Secret Service knew of his activities so that when he returned to Ireland on Good Friday 1916 on a German U-boat for the Easter Rising, he was captured on Banna Strand outside Tralee and brought to London where he was hanged for treason. Given his international reputation, a campaign for reprieve was organised, however the British Government stymied serious support for the reprieve by sharing extracts from Casement’s private diaries in which he detailed his enthusiastic sex with men. How Casement uses his body and places in relation to others was not something endorsed by the colonial choreography of the time. The treatment of Casement’s body is a clear reminder that the personal is political (which means that the state is there in the apparent privacy of our bodily intimacy but it also means that when we make changes on the level of our bodies that it can have political ramifications) as his sexuality becomes a matter of state, discussed at the British Cabinet, where civil service papers presented to counter arguments for a reprieve of the death sentence describe Casement as having:

‘completed the full circle of sexual degeneracy from a pervert to become an invert, a woman or pathic who derives his satisfaction from attracting men and inducing them to use them. (Cabinet memo July 15 circulated July 18)’

You can hear the attitude to women implied in this characterisation and the proper relations of male and female bodies it entails…

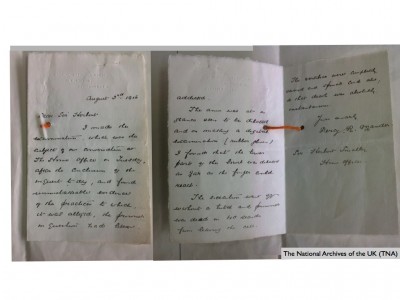

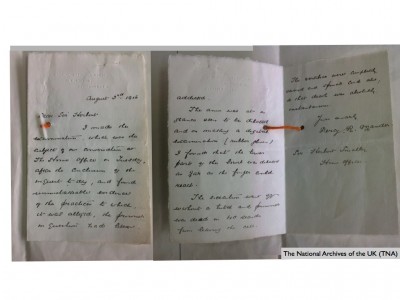

The state’s concern with Casement’s body continues after his death: At the National Archives in London, a letter from the Doctor (Percy r Mander) at Pentonville Prison where Casement was hanged describes how he examined the body immediately post-mortem to determine if Casement could have had the sex he describes:

‘ I found unmistakeable evidence of the practices to which it was alleged the prisoner in question had been addicted. The anus was at a glance seen to be dilated and on making a digital examination (rubber gloves), I found that the lower part of the bowel was dilated as far as the finger could reach. The execution went off without a hitch and the prisoner was dead in 40 seconds from leaving the cell. The vertebrae were completely severed and spinal cord also, so that death was absolutely instantaneous.’

The National Archives of the UK (TNA)

And beyond this post-mortem investigation, Casement’s bones were a subject of discussion between the British and Irish governments, with the Irish supporting Casement’s family’s request to have him reinterred in Ireland. Just ahead of the 50th anniversary Easter Rising, Harold Wilson, Labour Prime Minister and perhaps mindful of the votes of the Irish working class in Britain, agreed to return the remains, though of course Casement’s wish was to be buried in Antrim but such a burial wouldn’t constitute a repatriation. So he is buried in Glasnevin instead. Where bodies go, what they do is political.

A number of things have drawn me to Casement as a resource for imagining a hospitable national body. Of course, his is a scandalously hospitable, permeable body. It is also constantly mobile. He never had a permanent home but was always in transit, a choreography that was necessary, perhaps, for someone who wouldn’t settle in the patterns of the nuclear family. When he was tried, he was described as being of no fixed abode. His diaries detail how he even managed a day-trip from London to Dublin and back again, the kind of trip that cheap air travel has made possible for some of us, but which was much more of a feat a hundred years ago.

Photo Ste Murray www.ste.ie

He is also important to me because of how he connects nationalism to international justice. So he reminds me that we cannot think of a flourishing national body without taking in to account our responsibilities to those who are beyond our national borders. But then he also reminds us that borders are fluid. Born a Protestant, dying a Catholic, British peer Irish revolutionary, part of the establishment and simultaneous criminal. Incidentally the same law that criminalised his homosexuality was in force in Ireland until 1993, the year I started training as a dancer. Casement was also sensitive to bodies, to the length and heft and beauty of men he desires, but also to the suffering of abused bodies in Africa and the Amazon or under-nourished bodies in the West of Ireland. This part of the 1916 legacy is not something I was taught growing up in Ireland, and in our moment of centenary commemoration, I want to communicate the value of a deeper understanding of bodies, of their potential, of their diversity. It’s not only dance that can communicate this understanding but I do think that dance has insights that are valuable in helping us to expand our physical potential and movement possibilities.

In practice The Casement Project has five main elements:

A stage performance that will premiere in June in London, less than two miles from where Casement was hanged. It will be also be presented in Dublin and Belfast later in the year.

Having the premiere outside of Ireland felt like a useful way to make sure the national commemoration didn’t become inward focused, and besides, as part of the 1418now Centenary Commission programme, it also queers that World War One narrative in a way that seems important to me.

On 23rd July, we will have a day of dance on Banna Strand, called Féile Fáilte to welcome the stranger ashore but also to celebrate the stranger who is already part of each of us.

I’m making a dance film with Dearbhla Walsh to be broadcast on RTÉ

I’m organising two academic symposia. The first, happens on 25th February at Maynooth University and is called Bodies Politic and will look at how some of the artistic projects commissioned for 2016 are addressing the body and commemoration. On 3 June, The Hospitable Bodies Symposium will take place at the British Library, connecting Casement’s legacy to the work of contemporary artists

And finally there is a series of engagement opportunities for people to join in the project, which includes workshops with LGBT refugees in London and participatory work in Tralee that will be shown at An Fhéile Fáilte.

A sixth element in the project is the talking about it in a way that starts people to think and invites them to become involved. It’s what I’m doing here today. It’s a privilege to be with you, to have this voice on this platform, but I’m suspicious of myself talking. And so the finish today I want to show you the briefest of glimpses of the dancers in The Casement Project in a trailer by DRAFF magazine, a beautiful and free magazine about theatre and performance that I’d urge you to pick up around town. It’s got more information on The Casement Project in rehearsal if you’re interested. I want to finish with it because it’s the dancing that matters. But I hope placing my body for the first time on this important national stage in front of and alongside you, that it also prompts a physical response.

When the dance film, Match was shown on RTÉ, it was discussed next day on a radio chat show where one man phoned in to say, ‘I have no idea what that was but I couldn’t stop watching it’ . That matters to me because it suggests a connection, one that doesn’t yet or may never have words to describe it. We deserve a new state where such valuable knowledge can be acknowledged and built on.

[The short DRAFF trailer I showed is here]

https://www.instagram.com/p/BAb68VrBEys/?taken-by=draff_magazine