It wasn’t until the a couple of hours before the performance at the Bluecoat in Liverpool that I read the wall text that accompanied Bisakha Sarker’s installation. I’d arrived to perform in ACE-supported collaboration with pop band Stealing Sheep and contemporary music ensemble, Immix as part of The Liverpool Irish Festival. I’d planned to be dancing alongside Aoife McAtamney but a last-minute illness prevented her from performing and so the planned duet became a more improvised 30 minute solo on a raised cruciform platform flanked by musicians.

I’d been passing the installation on the way to and from the rehearsal space and was taken by the lustrous projections of an older woman (b is in her seventies) in a predominantly red sari.

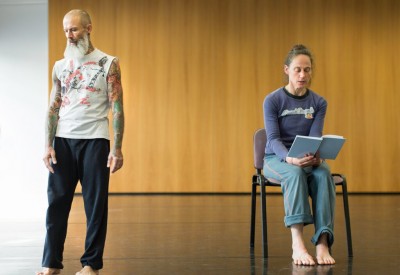

On Sunday, before the show, I was a little daunted about the prospect of performing on my own. The collaboration had happened virtually with demos of Stealing Sheep’s music arriving via Dropbox and Daniel from Immix explaining via email the structure of the composition. But it wasn’t until Saturday, the day before the performance, that Aoife and I heard the whole sequence of music and on Sunday, by the time it was clear that Aoife would not be able to dance, I was hearing the whole sound of Stealing Sheep and Immix Ensemble together for the first time as I figured out what I could do. But what a sound. I accepted the invitation from Laura Naylor of the Liverpool Irish Festival because while I liked what I heard of Stealing Sheep and Immix’s separate work, it wasn’t music I’d usually choreograph to. But I think it’s important to get beyond your habits and comfort zones, even temporarily, so you can find new things and maybe return to the familiar approaches with renewed insight and understanding. Seeing Stealing Sheeps slick, graphic image, I wasn’t sure how my more organic, raw style would sit with their sound, but Cunningham and Cage have taught me not to worry too much about such things. I described our collaboration as a salad of tasty ingredients, rather than a stew. We didn’t have much time to have our flavours blend into a stew but could trust the audience to do some of the digestion for us.

Without Aoife, it felt like a bigger challenge to meet the music as an equal element in the collaboration. It was clear that this was a gig format rather than a dance show. I was dancing on a platform but the audience was standing and there was a support act before it. Knowing it was a gig was an ease in some ways: most people would be there to hear the music and there would be fractal projections over the stage that they might find a more familiar visual accompaniment. But I didn’t want to be a backing dancer in that scenario.

Reading the text accompanying Bisakha Sarker’s installation, I discovered that she is a dancer choreographer now in her seventies who worked with a contemporary choreographer to explore new ways of moving in her mature body. She was inspired to keep dancing by a quotation from Tagore, ‘Do not fold your wings’. Seeing these words and her image inspired me in turn to keep enjoying the dance I am able to do, to enjoy the spread of my wings, their beating and where they carry me.

The performance seems to have been a success. I did feel that it took the audience a while to know how to see me in this music context but gradually, as I fed from the music and the musicians, and unravelled the movement material and ideas I’d brought, I felt part of the bigger sonic, kinetic and visual energy we created together. I’m grateful for all of these opportunities to be dancing with and for people. And I hope that I will be as brave, curious and creative as Bisakha Sarker.