Ellie O’Byrne hosts a weekly arts and culture show in Cork. She came to see a run of The Rhythm of Fierce during our final week of rehearsals at Firkin Crane and when she joined in the dancing herself at the end of the run, I knew she’d be a sympathetic interviewer. Here’s what we talked about:

Dance democratisation: Review of Cure at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre

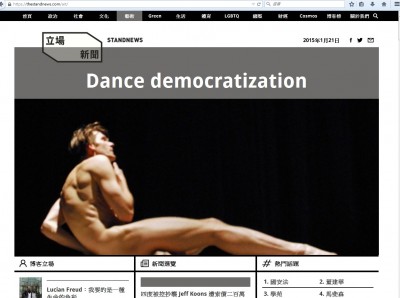

Dance democratisation

Joanna Lee

https://thestandnews.com/art/dance-democratization/

“Democracy” is Hong Kong’s keyword of the year 2014. “Democracy” is a fragile word because it dies with attempts on its own definition. It is also a slippery word because it invites imagination and interpretation of all sorts. To me, one can almost place “democracy” and “dance” in the same cognitive bucket, the former being an idea and the latter being its expression. If democracy absolves standard of practice from one single source of authority, if it requires courage to openness and admission of differences to propagate, I propose that “dance democratization” has been diligently put into action in two works shown during i-Dance (HK) 2014 in December.

Who makes dance? What qualifies a dance-maker? CURE by Irish dance artist Fearghus Ó Conchúir is an one-hour performance made up of six parts, each created by an individual who may possess dance background, or may not. Ó Conchúir stitches these parts together – seamlessly, without sacrificing any trace of the creator’s distinctive touch. One can easily tell one part from another because they are so different, yet they exist peacefully alongside one another like fetuses sharing the womb. If choreography is about the placement of the body in the space and each of us manifests our existence through this vessel named “body”, it is just natural that everyone has his version of choreography. If dance-making is about epitomizing the body as a medium of communication, this is what the performance is about.

“What does it take to recover” is the question behind the CURE concept. The dance-makers investigated the emotions they went through when they fell, and how they picked themselves up. Ó Conchúir, the interpreter of these emotions, demonstrates his powerful expressiveness with his intense concentration. He thinks before he moves, he moves what he thinks. The “dance” is Ó Conchúir’s meticulous control of his muscles and joints. The “movements” are everything that proves his presence, from his breathing to his jetés. The contemplation and the honesty are what draw the audiences to him. In the first part of the performance, Ó Conchúir moves around in a square box of light by the left side of the stage. His manner is carefree, his shifts jumpy. It is a sad view to watch him swing his long limbs in his grey tracksuit: it is as if you see a child playing happily inside a cell, not knowing he has been deprived of a world much bigger than this. In another part, Ó Conchúir sits on the floor at the center of a circle of chairs. He slowly pushes the chairs away from him with his legs. The noise of the legs of the chairs scratching the floor is the muted scream of Ó Conchúir’s, whose over-stretched chin muscles fail to make any sound. In yet another part, the naked Ó Conchúir kneels on a piece of silky fabric. With ritual-like dedication he flexes and relaxes his muscles, sweat rolls down as he breathes in and out to fuel his seemingly subtle movements. Finally, he lays face-down on the fabric, allowing the sweat to stain the piece, leaving marks of his existence.

If democracy is about the respect for participation, Tian Gebing’s first-ever choreography, Non-Fat-Thug-Waste, is a nice experiment of the cross-breeding of a dancer-maker. Tian is the founder of Zhi Laohu (The Paper Tiger), a theatre group based in Beijing known for its subversiveness. Trained as a stage director, Tian just knows enough about stage performance for him to denounce the reliance on the script, or verbal delivery. His choreography is to place two powerful bodies, those of Gong Zhonghui’s and Wang Yanan’s, into the space and interact with time, that is, to move, either in connection to or against the verbal instructions given by Tian. Both Gong and Wang are seasoned dancers, but in very different ways. Throughout the performance, the skinny Gong repeatedly throws herself to the floor or dashes from one end of the stage to the other, hardly catching her breath. Wang, plump and sexy as a Dunhuang dancer, elegantly moves her wrists and fingers and head, making a step only once in a while. The “dance” actually takes place on her face: her facial expression changes from a smile to a frown then to a sob then to a scream while her fingers twist and her wrist joints rotate. She makes up her share of the “moves” towards the end of the performance when she ties the end of her braid to a wire hanging from the roof. Then she slowly walks away from the wire until it pulls her braid so hard that you can see her hair standing on ends on her scalp. She talks, she laughs, she cries while she walks, in silence. When she cannot go any further without tearing a piece off her scalp, she all of a sudden regains her composure, releases her braid and stands still.

To me Tian has no doubt made a dance. He has demonstrated his ability to identify the power in two bodies and through them deliver his contemplation on the nature of performance: What is it? Who decides what happens on the stage? What makes an audience listen? He doesn’t design movements, he probably cannot. But he respects movements and the bodies that make them, and more importantly, he believes in the instantaneous expression by the powerful bodies he has identified. He creates the space for honesty to flow, from the performers to the audiences.

Postmodern dance-makers have been expanding the possibility of stage representations by working with artists across of art forms and applying multi-media elements such installations, sound, video, computer applications, and other you-name-it. In these two performances we see “multi-media” being an adjective of the dancer-makers’ background instead of the accumulation of stage techniques that take attention away from the body. If democratization embraces openness, it invites challenges and new ways of doing. The aesthetic lies in the forte of one’s urge to communicate, in how the dance-makers and their interpreters together devote their utmost attention and “training” to the body as the ultimate medium of manifestation.

In 2014 we practiced the choreography of placing our bodies where they should be for causes we believe in. We witnessed the power of the body’s presence in the space. We saw actions growing into movements. We saw dance.

—

In review are:

CURE in the i-Dance 2014 “Solo & Improvisation” series, Dec 12, 2014 at the Studio Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Center; Non-Fat-Thug-Waste in the i-Dance 2014 “New Dance Platform” series, Dec 19, 2014 at the Black Box Theatre, Kwai Tsing Theatre.

L’intime – at the Tipperary Dance Platform 2014

As part of their residency in the county, Jamzin Chiodi and Alex Iseli have been running the Tipperary Dance Platform for the past 5 years. TDP’14, to which they invited me this year as a mentor, includes a week’s laboratory and mentoring for emerging dance artists, as well as performances, work-in-progress sharings, and classes that are open to all. This year, the performances included an exceptional duet, Embrace, by French-based Affari Esteri, a sean-nós dance class with the legendary Roy Galvin and selection of dance films. A particular pleasure for me was taking classes with Edmond Russo and Helene Cathala, dancing alongside a young generation of dancers in Ireland and also learning through Helene repertory material from a Cunninghamesque Bagouet, Trisha Brown, Liz Roche and Helene herself. It was a privilege to have her embodied knowledge of those different traditions of dance-making offered to us so clearly and articulately, and to feel that knowledge call to some of the traditions that are part of my own embodiment.

Participation in the platform was free, as was attendance at most the events. Yet for the most part, the public events at the Excel were attended by the dance community of Irish and international artists who were participating this year or who had participated in previous years. Notable by their absence from the performances was a public beyond the profession and its intimates.

The topic for discussion at the Saturday afternoon public forum was l’intime – the intimate space. The choice of this topic was prompted by a feeling that Alex and Jazmin expressed about the challenges of staying true to the validity of their intimate/personal artistic preoccupations while wanting to share that experience with a wider public.

In how Alex described l’intime there was a strong sense of a space that existed just around his body, close to it but also boundaried. Discussing how we might translate l’intime in to English, I realised that it was different from ‘intimacy’, since that term in English already implies a relationship with an intimate person that l’intime does not yet include. It struck me that thinking about how to reach beyond a boundaried personal space like l’intime is already made difficult by the fact that one has drawn this boundary.

In my presentation to the forum, I proposed that we recognise the intimate space as already made by external influences. Psychoanalysis suggests that the most intimate psychic urges are shaped by the family relations of the child. Marxism suggests our relationships are governed by the forces of capital. Foucault proposes that how we experience and understand our ‘selves’ is shaped by power relations in which we participate. The ‘external’ world is already ‘inside’. For some, this is a depressing thought, as it seems to lead to a situation where we have no individual agency. However, an alternative way of looking at it is to recognise that if the world is already ‘inside’ individuals, already in their intimate space, then working on that intimate space is already an engagement with the world. It is not then a question of artists needing to justify or get over their focus on the personal to reach to a wider public ‘beyond’. It is rather a recognition that in having the courage to take as their material the intimate experiences of their lives, in confronting in that intimate space the many external forces that shape the personal, and in working through the conflicts and lack of resolution between those forces, dance artists can re-imagine and embody possible outcomes for how those forces operate.

As Hélène Cathala observed that sharing the space of intimacy is about risk. It’s not just about cosy familiarity. Apparently the root of ‘intimate’ contains the Latin ‘timere’, to fear, so that intimacy is about being able to be in a place of fear with another. This fear gives a charge to l’intime that Helene also reminded us was often connected to sex. For the dance artist to work with l’intime therefore is to work not with a boundaried, reliable personal identity, but to work with an individual experience of the an identity under construction, dissolution and re-construction at the nexus of multiple ‘external’ forces that are also being transformed by this individual working out.

Shadowing all of this discussion in Tipperary was a question about solidarity, a question of particular relevance to dance artists like Alex and Jazmin who work in a context where their skills and knowledge are unfamiliar to most people. How do they maintain the energy to undertake the risky artistic enquiry that motivates them? How do they do it when they have a sense that their context is foreign for them and they for it? (Alex mentioned that one of the reasons that I’d been invited on the panel is that I, along with Dylan Quinn, would have an ‘Irish’ perspective on l’intime that he expected to be different to the ‘Mediterranean‘ perspective that he, Jazmin, Helene, Edmond and Shlomi would have) I was struck by Dylan’s observation in the forum that at the time he was returning to set up his dance practice in Enniskillen he thought the hardest thing about doing so would be the lack of financial resources. However, what has proven to be most difficult is that fact that there are so few people (not even artists of other disciplines) that understand what he wants to do in dance and instead ask him about Zumba classes and wedding dances. For pragmatic reasons –primarily to support his family– he now gives those Zumba classes and teaches wedding dances and he is proud that he can bring dance experiences to four generations in his community of place, from toddlers to the elderly. But it is not a community that, for the most part, understands his artistic practice.

As Jazmin expressed her happiness that the forum provided her with an opportunity to share her thoughts and concerns about this topic, It occurred to me that in a context where the particular support of an artistic community isn’t available, what Alex and Jazmin are doing in the Tipperary Dance Platform is to curate their own community of support. It is a generous curation, making opportunities for dance enthusiasts, audiences, and professionals at different stages of their careers from Ireland and abroad. It is an act of community building that relies on their hard-work, sustained discipline, creativity, resilience and a network of personal and professional relationships. It does also need funding and infrastructure, even if the actual money is in no way commensurate to the work they and their network put in to making the platform happen

[ca

New steps with old friends

I met Stéphane Hisler in Dublin in 2007 when I was Artist in Residence for Dublin City Council and when he was dancing there for other Irish choreographers. Since then he’s been part of the creation of and performed in a number of my works (Niche, Three+1 for now, Sweetspot, Tabernacle), contributing his characteristic passion, fierce physicality and generous support. More recently, we’ve swapped roles when I asked him to be one of the choreographers of Cure.

I met Stéphane Hisler in Dublin in 2007 when I was Artist in Residence for Dublin City Council and when he was dancing there for other Irish choreographers. Since then he’s been part of the creation of and performed in a number of my works (Niche, Three+1 for now, Sweetspot, Tabernacle), contributing his characteristic passion, fierce physicality and generous support. More recently, we’ve swapped roles when I asked him to be one of the choreographers of Cure.

Our work together has been based on a shared physicality, though I am not as physically fearless, gifted or strong as he is, and it was encouraging to work with him on Cure in Melbourne where he now lives, to find that I still have some of that energy in my body.

Geographical distance between us makes it less easy to find opportunities for Stéphane and I to work together. Cure proves it’s not impossible. Stéphane’s work with Snuffpuppets (who hosted the Melbourne leg of the Cure creation) provided another opportunity recently when he toured with them to Romania and got in touch to say that he wanted to use the trip for us to maintain a dancing connection too.

We rehearsed in Walthamstow at the KNI Foundation studios where I made Porous last year. It was a pleasure to make the short trip there each morning, to dance alongside Stéphane, sharing a familiarity of physical commitment and building on that familiarity to find what we could communicate next through it. We spoke of the value of our shared history in dance and in friendship as a choreographic resource, a shared history that is already a material to work with. I’ve become increasingly conscious of my appetite to acknowledge, draw on, strengthen and energise the networks I’ve established over the years. These networks are professional and international but they are also networks of friendship that teach and support me. Despite being international, geographically dispersed and irregularly activated, I trust these relationships and the care they provide.

I brought to our research my ongoing preoccupation with permeable borders, introducing the notion of smear that I’ve taken from the paintings of Francis Bacon. In many of Bacon’s paintings, I see the organic viscerality of human shapes smeared against linear frameworks and cages. The human body exceeds its corporal borders, (violently, erotically) but does so in relation to external formal structures. Smear wasn’t difficult for Stéphane and me since our dancing together invariably produces sweat and a slippery contact that generates movement beyond the direct lines of pressure and intention. Sweat crosses the body’s skin border, and does so involuntarily. It is not really consciously controlled even if we can generate the conditions that call it forth. Emotional states such as fear also generate sweat as an involuntary exceeding of physical containment. Sharing sweat creates a space of mingling of our insides in a shared point of generative contact. Bacon’s studies of wrestlers in quasi-sexual, quasi-combative intertwining came to mind in parts of our movement.

We finished the week with physical material, with ideas and with an appetite to give further shape to this work. It’s good to have a shared project to plan for.