Things I’ve learned:

That I’m not alone

To ask for help

To trust instinct

To practice

To be disciplined

To work hard

To listen to when it’s time to ease off

To take a risk

To soften

To enjoy the power I can muster in my body

To access and harness the emotional energies, such as anger, that I usually avoid as negative

To keep learning

To honour what I’ve already learned

Cure: Things I’ve learned

Cure – Final rehearsals before the premiere

It’s been an effort to make myself write about the final rehearsals and first public performances of Cure. It’s not that writing and reflection isn’t important but I, with the help of others, have put much energy, focus and attention into the embodiment of the work, particularly in the concentrated form of a performance, and writing about it doesn’t have the compelling necessity that dancing it does. Maybe the difference is obvious from that last phrase – to write about it (outside it, around it, at a remove) and to dance it (do it, be it, no space between). That doesn’t mean that I’m not happy that Cure might stimulate others to respond in a variety of ways that include talking and writing.

In the first week of final rehearsals in Dublin, I organised with Create and The Dublin Dance Festival to host a supper at The Firestation Artists’ Studios where, over home-cooked food, we could discuss cure from different perspectives. The idea of having such a supper came from the very enjoyable lunch I was asked to curate for Metal as part of their Liverpool Biennial activities last year. At the supper, care and attention was given by Katherine Atkinson and Patrick Fox of Create in preparing food and the space, and by Julia Carruthers and the whole team at the Dublin Dance Festival office who prepared food and helped generously with the serving on the evening. I expected that I’d have to do the food preparation myself, and I did make enough soda bread to feed 50 people!, but I was very grateful that people who were very busy themselves took the time to help. For the 20 or so people who attended, I facilitated conversation about what cure and recovery might mean, and we encouraged the guests to leave notes on the table cloth and write postcards about what they were taking away from the event.

However, beyond this discursive element, there was an engagement that happened at another level, a connection to self and others that happened in the short qi gong warm up I led, in the gathering around a table to share food, in the time taken from other concerns to sit with strangers and listen. Whatever the discursive outcome of that supper, I was happy that we had, through care and thought, created an atmosphere that connected people in warmth, enquiry and openness. And this was already part of Cure, if not one that would be directly manifested in the performance.

The first week of my final rehearsals at Dancehouse, I taught professional class. It’s been a growing pleasure to find a dynamic and skilled dance community taking class in Dublin. Part of the pleasure for me comes from seeing familiar experienced dancers sharing the space and energy with a new generation of performers. In the context of Cure, I was glad to be able to share some of the old knowledge in my body with this group. And it was good for me to start each day with the energy of a group to lead me in to my own rehearsals.

One of the things I noticed straight away in the studio was that it was unfamiliar to have a production team (Ciarán the lighting designer, Alma the sound designer, Mags the stage manager) sitting in rehearsals watching me. When I’ve made solo work before, I haven’t had a team to help, and when I have had a production team, it’s been making work like Tabernacle where there’s been a group of dancers for me to focus on, while the production team watch and take the information they needed. For Cure, I had to manage my own sense of having to display something for the people watching. I also had an immediate sense of guilt that other people’s energy was directed towards me. But once I established a rhythm to rehearsals (warm up, run on my own, lunch, warm up for the team, notes and discussions), the guilt eased and instead I felt energised by the supportive watching. I knew in their watching Alma, Ciarán and Mags were trying to make sure that the performance would be as good as it could be. It quickly made sense to me too that they should be in the studio since, even though it’s a solo, I never imagined Cure as a solitary procedure. It was always designed to be made with others (the choreographers) and directed to others (the audience). Being in the studio on my own was fine at the beginning of the day but solitude wasn’t the goal and it wasn’t a useful thing to practice since the real task was to understand how the material of Cure worked with an audience and how I should be to mediate that relationship.

In addition to the production team, I opened rehearsals to whoever wanted to come to see the afternoon run-throughs. It was very helpful to practice being nervous in front of people and to experiment with how to present the material to them in different ways.

I became nervous again when it was time for the choreographers to gather and see the work. It was instinct that made me set about making Cure in the way we have. And I responded to that instinctual impulse by organising a structure that seemed fair and could be explained: two weeks with each choreographer, asking each one to make a 10 minute solo: but I didn’t really know how all of that would work out. I’d left a two-week rehearsal period at the end to give myself time to work on assembling the whole piece and I’d left some time with the choreographers to use their perspectives to help with that. In actuality, by the time I arrived in Dublin to start the final two weeks, it was very evident to me how the piece would be put together. I saw that I could go through the different solos in a particular order that made a dramaturgical and choreographic sense. I’d lived with the material in my body, some of it from over a year. On the first day of rehearsal in Dublin, I rehearsed and ran together the first three parts. On the second day, I ran through the other three parts in order. On the third day I ran all six in order and that order didn’t change between then and the premiere. Of course there were daily refinements of and experiments with how I made my way from one part to the next. I didn’t want the piece to feel like six separate solos with six beginnings and six endings. I wanted to maintain the sense of six distinct phases, six different perspectives, but also to create a flow from beginning to end that connected everything. I wanted an audience to see that these different perspectives were carried in a single body. This approach mirrors how I’ve worked with the choreographers as performers and collaborators, respecting their individual contributions, valuing their idiosyncrasies but holding them all together in a structure that makes it possible for others to respect and value those differences too.

In retrospect, it is obvious to me that this is how Cure should be and it is that instinct that was at the genesis of the idea for Cure. But having the instinct isn’t the same as being able to articulate it. I’ve tried to keep the choreographers up to date with how I’ve seen Cure evolve and to communicate to them what I thought the outcome of that evolution would be but I didn’t know as they arrived in Dublin to see the piece, if what I described matched their expectatations. I was clear that I wanted to show them the whole piece together before we worked individually on their sections. Elena and Stéphane arrived in Dublin earlier in the week and had a chance to give feedback already but the Friday before the Wednesday premiere was the first time the others saw the whole thing. It was a little daunting to have their six chairs lined up at the front of the studio and also a little strange to see so literally the reversal of our previous positions. But, as I’d trusted, they were very supportive. They had plenty of notes and refinements to offer and we did discuss whether we should try another order but it became clear that the existing version worked. So we didn’t change. It was a great relief that people felt I’d taken on their material and made it my own as a performer without compromising the integrity of their creation.

Though each of the pieces has a distinct movement quality, I was pleased at how readily connections between them offered themselves up.

Mikel’s part used blankets and Stéphane’s part a rug so it made sense to me to substitute a blanket for the rug and condense the materials in the piece.

Mikel’s part used blankets and Stéphane’s part a rug so it made sense to me to substitute a blanket for the rug and condense the materials in the piece.

Matthew’s section required chairs and Bernadette had mentioned the possibility of including a chair in her part so I proposed a way to do that which wove the chairs further into the choreography.

Matthew’s section required chairs and Bernadette had mentioned the possibility of including a chair in her part so I proposed a way to do that which wove the chairs further into the choreography.  Stéphane had created the solo with a latex prosthetic that for practical reasons was difficult to integrate into Cure. However, without having seen Stéphane’s work, Sarah introduced latex in a different form in her contribution. She had hoped to have a lump of concrete in her section but we didn’t find a way in for it. Instead that concrete (a particular lump that was used to smash the back window of Sarah’s car when we rehearsed in Limerick. We had already been discussing concrete as a toxic legacy of Ireland’s housing boom with concrete foundations underneath the withering ghost estates) helped crystalise a moment in Stéphane’s section that needed a material manifestation in the absence of the latex prosthetic.

Stéphane had created the solo with a latex prosthetic that for practical reasons was difficult to integrate into Cure. However, without having seen Stéphane’s work, Sarah introduced latex in a different form in her contribution. She had hoped to have a lump of concrete in her section but we didn’t find a way in for it. Instead that concrete (a particular lump that was used to smash the back window of Sarah’s car when we rehearsed in Limerick. We had already been discussing concrete as a toxic legacy of Ireland’s housing boom with concrete foundations underneath the withering ghost estates) helped crystalise a moment in Stéphane’s section that needed a material manifestation in the absence of the latex prosthetic.

Elena’s folding choreography found echoes in the folded blankets, chairs and latex across the piece. And beyond the piece. As we filled the bar in Project Arts Centre with the 1000 cranes we had each made as part of her task in preparing me for her choreography in Cure. The multicoloured cranes transformed the industrial feel of the bar in a way that a significant number of people were moved to comment on. Like all such transformations, it took a lot of work to achieve – not just the months of folding by Elena and me to make the cranes – but a group effort to hang and arrange and fire-proof them. It was good to feel that we gave the audience some simple delight as a prelude and coda to the performance.

The naked truth about dance

Michael Seaver wrote an article in the Irish Times about nudity/nakedness in dance and asked me to contribute to it alongside Aoife McAtamney and Nina Vallon, and Fitzgerald and Stapleton. The variety of perspectives is instructive: gender plays a part in how nakedness is received, though the different approaches of Aoife and Nina and of Áine and Emma suggests its not just about gender. Reflecting on the article and the work of the artists involved, I think female nudity is more readily commodified (‘lads’ mag’, artistic muse)and can therefore be less remarkable than male nakedness. However, female nakedness is even more challenging than male nudity when it refuses to conform to the conventions of commodification in the way that Fitzgerald and Stapleton definitely enact in their work.

Though he understandably didn’t include all of my responses in the article, Michael asked me some thought-provoking questions. Below are the questions and my responses

1. What has been the impulse to present a nude body onstage in your work? Where did that decision come from?

I wouldn’t say I have an impulse to present nudity on stage. I don’t give much thought to nudity. I don’t give much thought to tendu or

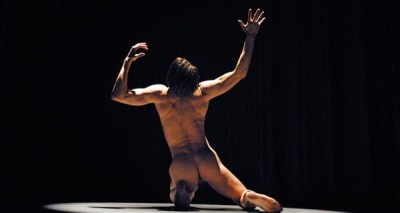

turn either but they’re often in the choreography as a means to an end. Nudity is a tricky notion anyway. You’ll already know Kenneth Clark’s distinction between the (aesthetically acceptable and supposedly not titillating) nude and the rawness of the naked. I think that nakedness emerges in some of my work because I’m not afraid of it. If it seems necessary or useful in the pursuit of a choreographic idea then I’ll follow it. So for example in Tabernacle, Matthew was naked near the beginning of the piece. That material came about because I’d asked the dancers in rehearsal to think about what they wanted to leave behind and Matthew had an idea of shedding skin and he undressed laying out his clothes like shed skin on the ground. I never ask the performers in my work to be naked. They offer it as part of an idea if it makes sense to them. Equally, if I’m performing, as I am in Cure, I’ll offer nakedness if it makes sense to me. So in one section where the intimate relationship between a piece of fabric and my skin is important, it made sense to me to take away all the other barriers – clothes – between me and that fabric. The result is nakedness but it’s not the aim.

2. In what way(s) can nudity be artistically meaningful?

When we were making Mo Mhórchoir Féin for the RTÉ Dance on the Box series, there was some question about how my near nakedness in a church would be received. It was suggested that I wear something else, maybe even a flesh-coloured body suit. Those options made no sense to me since the vulnerability of the naked body was important to the impact of the work, as was its implied sexuality. More importantly, the near-naked body of the male dancer in the church has a central and overwhelmingly authoritative precedent in the space already – the figure on the cross. So in that case, the unclothed body was a necessity. It wouldn’t make sense otherwise.

3. Can you relate nudity to your overall artist vision for Cure?

The physical nakedness in parts of Cure might be related to a willingness to be bare, to be open, to show things as they are rather than hide. I think the choreographers who’ve contributed to the making of Cure all have that impulse to honesty and openness that makes them great performers and artists and they’ve each found ways to reveal and lay bare what they think matters about cure. And in some instances, that laying bare is literal, not because they required it of me, but that their idea was best expressed by being naked.

4. How does it feel different performing nude than clothed?

If the choice is right – the right clothes, the right nakedness – then it’s not where my attention is in the performance. If the clothes or nakedness make me self-conscious then they’re the wrong choice. I performed the solo from Cosán Dearg in the middle of a busy art gallery in Beijing with lots of people taking photos on their mobile phones but the nakedness for the solo was right and so I didn’t feel exposed or vulnerable in that was potentially a weird situation.

5. How soon in your creative process to you think about costume?

The sooner the clothes are integrated the better. (Though I’m not as organised as Raimund Hoghe whom I heard has the dancers costumed before starting rehearsals and I can see how that makes sense) How we move is altered by the textures on our body, the tightness or freedom of a cut, or by the sensitivity of exposed skin. It doesn’t make sense to practise and practise movement material and not practise as sensitively the way that clothing or nakedness impacts on that movement. It’s not that it’s always about selecting clothes that are free: maybe one wants a particular restriction. In Cure, I wear shoes for some parts and that changes my relationship with the floor. It makes some movements easier because the shoe protects my feet but it changes others, like turns. But if executing a perfect turn was the objective then we’d make a different costume choice. For Cure, that’s not the objective! So no last minute trips to Penney’s – the clothes will be as familiar and worn in as the movement.

Cure – Dublin Dance Festival – first reviews

‘The lighting design is subtle and effective, and the soundtrack, which is occasionally unsettling, provides the perfect accompaniment to this performance. Fearghus Ó Conchúir is exceptional, a very talented performer….The piece was choreographed by a team of six, and there is a sense of the collaborative effort here. It is profoundly emotional, hopeful and thought-provoking, and is highly recommended.’ Una McMahon, entertainment.ie

‘A sequence of abstract meditations on the theme of recovery, bound together through the still centre that is Ó’Conchúir’s presence on stage, ‘Cure’ is not about the sum of its parts; rather, it’s about bringing attention to how necessary each of those individual, underlying parts are in the construction of a whole.’ Rachel Donnelly, DDF Blog

‘Fearghus Ó Conchúir puts his own eloquent body firmly on the line in this exposing, sometimes moving journey from fall to recovery. We are absorbed by his hugely focused presence and arresting movement, each small gesture carefully controlled, each flexing muscle intimating a small step forwards or even sideways on the road to healing.’ The Irish Times